Parashat Mattot-Massei: Numbers 30:2-36:13

Series:

A Lesson of Priorities

Now the people of Reuben and the people of Gad had a very great number of livestock. And they saw the land of Jazer and the land of Gilead, and behold, the place was a place for livestock. (Numbers 32:1)

When we read the first verse of Numbers 32 in English it seems pretty normal. It tells us how the lush pasturelands of Jazer and Gilead were suitable for the large number of cattle owned by the tribes of Reuben and Gad. If we look at the Hebrew behind the first verse, however, we will find a much more dynamic description of what is taking place. Once we discover this we will learn a valuable lesson in priorities.

In Hebrew, this verse should initially get our attention because it both begins and ends with the same word: mikneh, or "cattle/livestock." It also contains word repetitions and several emphasis words, such as rav (great), atzum (vast/numerous), and meod (exceedingly/much). If we were to try and translate this verse awkwardly into English to retain the emphases of the Hebrew, it might sound something like this:

Cattle-abundant-had the children of Reuben and the children of Gad-great and vast amounts- and behold, they saw that the land of Jazer and the land of Gilead-that place-was a place for cattle.

The Torah has a wealth of knowledge to offer on the mere surface level. Often, however, it desires to teach us a deeper lesson that we are not able to perceive through our translations without assistance. Sometimes there is a lesson waiting to be learned just below the surface of the text if we will take the time to unearth it. After all, it is the glory of God to conceal a matter, but the glory of kings to search it out.

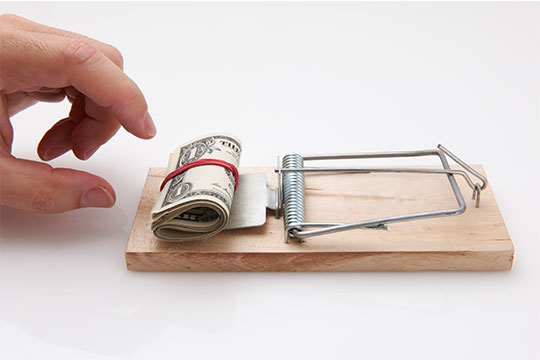

When we dig into this passage we should ask ourselves, "Who has who? Do Reuben and Gad have the cattle? Or do the cattle have Reuben and Gad?" It becomes immediately apparent that the Torah is about to teach us a lesson of priorities.

The tribes of Reuben and Gad are not only asking permission to stay behind while the other tribes go and fight to settle the land of Canaan, but they have their priorities all mixed up. They tell Moses, "the land ... is a land for livestock, and your servants have livestock" (vs. 4). When Moses scolds them, they respond by saying they will, "build sheepfolds here for our livestock, and cities for our little ones" (vs. 16) before they go and fight for the Land of Promise. Taking care of their children almost seems to be an afterthought in relationship to their plans for their livestock. Again, Moses has to correct them and straighten out their priorities by reversing the order and telling them, "Build cities for your little ones and folds for your sheep" (vs. 24).

Reuben and Gad had their priorities in their livestock. Moses wanted their priorities to be in their families. But the Torah had already foreshadowed this problem by telling us that the tribes of Reuben and Gad had more livestock than they knew what to do with. They had livestock. But was it really they who had the livestock? Or did the livestock have them? Where are our priorities? What do we think about and talk about the most? Do we have our possessions or do our possessions have us? The answer may be deeper than we think.